The Battle of Gettysburg took place from July 1st to the 3rd, 1863. During those 3 days, 8000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed and 27,000 were wounded. On July 4, 1863, Confederate General Robert E Lee ordered his Army from the battlefield and retreated back across the Mason Dixon Line towards the Potomac River. Union General George Meade gave chase and ordered his best surgeons to come along, leaving behind a woefully inadequate number of doctors to attend to the wounded of both sides who were still lying on the blood soaked fields of Gettysburg. Volunteers from across the Union were called to Gettysburg. One who answered the call was a young Quaker woman from South Jersey, Cornelia Hancock, who traveled to Gettysburg with her brother in law, Dr Henry T Child, who was a physician in Philadelphia. Cornelia was the first Angel of Mercy to reach the 3200 wounded soldiers of the Union 2nd Corps. Her tireless dedication won her the love and admiration of her patients and the respect of the Surgeons with whom she worked. Gettysburg was just the beginning of a long life of compassionate public service for Cornelia who was determined to leave the world a better place than she found it. This is her story.

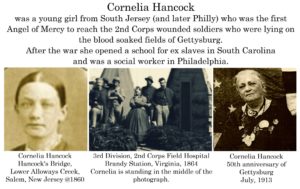

Cornelia Hancock was born on February 8, 1840 at the family ancestral home in Hancock’s Bridge, Lower Alloways Creek, Salem, New Jersey. Her parents were Thomas Yorke and Rachel Nicholson Hancock and she had 3 siblings: Ellen (1829), William (1832) and Thomas Jr (1842). Cornelia was a prolific letter writer and described her father this way:

“All through the township, my father was known as, Thomas Y the fisherman. He was a silent man who spent his time thinking and fishing in the little stream known as Alloway’s Creek, and I never knew of his having any other occupation except that of reading the newspapers. In order to fish more successfully, he went to bed with the tide and got up when it turned. He owned a canoe built to suit himself and to hold but one person. On it were painted the letters ItyT, the title having been invented with great care and ingenuity for the exclusive purpose of baffling idle curiosity. No one could pronounce the word or imagine what it meant, and it pleased him to never tell his numerous questioners that the pronunciation consisted in naming each letter separately. We lived on our inherited property and ate fish every day. As it was impossible for us to eat all of the fish father caught, a large number was given away to the village people, about six of the finest being reserved daily for our own use. It never occurred to my father to sell them or do anything else to add to the income of the family. We had enough to live on and if we wanted more we could get it ourselves.”

Cornelia’s younger brother, Thomas jr, died on June 23, 1851 at age 8. Later that summer, her older sister, Ellen, married Dr Henry T Child, a Philadelphia physician and abolitionist. The Childs would live at 634 Race Street (7th and Race) for nearly 60 years. As Cornelia grew up, she shared her father’s love of reading the newspaper. She was an intelligent girl and spoke with an honesty and bluntness that did not always sit well with their neighbors. By the summer of 1863, her brother William and all of her male cousins had joined the Union Army and were away at war. Cornelia desperately wanted to contribute, more than just praying for the soldiers and joining a sewing circle. She wanted to do something real, something that mattered. She told this to her brother in law Dr Child (who she always referred to as “Doctor”) and he promised that if he ever came across an opportunity for her, he would help her obtain it. That opportunity arrived on July 5, 1863. Word of the situation at Gettysburg had reached Philadelphia and Dr Child was gathering a team of volunteer nurses to accompany him to the battlefield. Dr Child sent his carriage to Cornelia’s home in Salem and she arrived in Philadelphia that afternoon. She was placed in the care of Eliza Farnham, another volunteer nurse, and they boarded a train at Broad and Prime (Washington) at 11pm. By the morning they were in Baltimore where Dorothea Dix, the Superintendent of Army Nurses, looked the new nurses over. She approved of them all except Cornelia, who she said was too young and attractive to be an effective field nurse. While Miss Dix and Miss Farnham debated the topic, Cornelia took the situation into her own hands. She simply got back on the train and refused to move from her seat. Miss Dix could like it or not, Cornelia was going to Gettysburg.

From Cornelia’s letters: “We arrived in the town of Gettysburg on the evening of July 6, three days after the last battle. Every barn and church had been converted into temporary hospitals. We went that same evening to one of the churches, where I saw for the first time what war meant. Hundreds of desperately wounded men were stretched out on boards laid across the high backed pews as closely as they could be packed together. I seemed to stand breast high in a sea of anguish. Too inexperienced to nurse, I went from one pallet to another with pencil, paper and stamps in hand, and spent the rest of that night in writing letters from the soldiers to their families and friends. To many mothers, sisters and wives, I penned the last message of those who were about to become “beloved dead”. Learning that the wounded of the Third Division of the Second Corps, including the 12th Regiment of New Jersey (with whom her brother William was attached), were in a field hospital about five miles outside of Gettysburg, we determined to go there early the next morning, expecting to find some familiar faces among the regiments of my native state. As we drew near our destination we began to realize that war has other horrors than the sufferings of the wounded or the desolation of the bereft. A sickening, overpowering, awful stench announced the presence of the unburied dead, on which the July sun was mercilessly shining, and at every step the air grew heavier and fouler, until it seemed to possess a palpable horrible density that could be seen and felt and cut with a knife.”

“There was hardly a tent to be seen. Earth was the only available bed during those first hours after the battle. A long table stood in the woods and around it gathered a number of surgeons and attendants. This was the operating table and for seven days it literally ran blood. A wagon stood near rapidly filling with amputated arms and legs; when wholly filled, this gruesome spectacle withdrew from sight and returned as soon as possible for another load. So appalling was the number of wounded as yet unsuccored , so helpless seemed the few who were battling against tremendous odds to save a life, and so overwhelming was the demand for any kind of aid that could be given quickly, that one’s senses were benumbed by the awful responsibility that fell to the living. Our party separated quickly, each intent on carrying out her own scheme of usefulness. Wagons of bread and provisions were arriving and I helped myself to their stores. I sat down with a loaf in one hand and a jar of jelly in the other and a dozen poor fellows lying near me turned their eyes in piteous entreaty, anxiously watching my efforts to arrange a meal. There was not a spoon, knife, fork or plate to be had that day and it seemed as if there was no more serious problem under Heaven than the task of dividing that too well baked loaf into portions that could be swallowed by weak and dying men. I succeeded however into breaking it into small pieces and spreading jelly over each with a stick. A shingle board made an excellent tray as it was handed from one to another. I had the joy of seeing every morsel swallowed by those whom I had prayed day and night I might be permitted to serve. An hour or so later I found boxes of condensed milk and bottles of whiskey and brandy. It was an easy task to mix milk punches and serve them from bottles and tin cans emptied of their former contents.” In another wagon, Cornelia found casks of wine and baskets of lemons. To every man who had a limb amputated, she gave a gill of wine and for the wounded still lying in the field with the sun beating down on them she made lemonade.

On July 8, Cornelia wrote to her sister, Ellen: “We have been two days on the field. I feel assured I shall never feel horrified at anything that may happen to me hereafter. There is a great want of surgeons here; there are hundreds of brave fellows who have not had their wounds dressed since the battle. Brave is not the word; more Christian fortitude never was witnessed than they exhibit, always saying “Help my neighbor first, he is worse”. For two weeks Cornelia worked tirelessly at the field hospital. As she quickly gained experience, her duties grew. Besides cooking and distributing food, she also changed bandages, supervised the laundry and wrote letters home for the wounded (which she disliked doing because their words often brought her to tears). So beloved had she come that the soldiers chipped in and had a silver medal made for her. The inscription on one side read “Miss Cornelia Hancock, presented by the wounded soldiers 3rd Division 2nd Army Corps” and on the other side “Testimonial of regard for ministrations of mercy to the wounded soldiers at Gettysburg, Pa – July, 1863”. On July 26, she wrote to her mother: “I received a silver medal from the soldiers which cost $20 (equivalent today to $400). I know what thee will say, that the money could have been better laid out. It was very complimentary though. You will think it is a short time for me to get used to things but it seems to me as if all my past life was a myth. What I do here one would think would kill at home, but I am well and comfortable.” By August, the field hospital was shut down and everyone was moved to the general Hospital at nearby Camp Letterman. Cornelia went along and was put in charge of Ward E which consisted of 4 tents of 12 men each (she had 36 Union patients and 12 Confederates). On August 23 she wrote to her mother: “I think war is a hellish way to settle a dispute. Oh, mercy, the suffering! All the worst are dying rapidly. I saw one of my best men die yesterday. He wore away to skin and bone, was anxious to recover but prayed he might find it for the best for him to be taken from his suffering. He was the one who said if there was a heaven I would go to it. He was not in my ward now, but I just went over in time to be with him when he died. I hope to keep well enough to stay with the men I am now with until they are all started on their way home to heaven or home.” On August 31 she wrote to her sister Ellen: “I like Mrs Holstein (Cornelia’s immediate supervisor) real well. I am most too smart for her though. I will get the things for the men without orders and she is a great respecter of order. I am considered the shiftiest woman on the ground.” I suspect that her relationship with Mrs Holstein deteriorated quickly because within one week of writing that letter to Ellen, Cornelia was back home in Salem waiting for a new nursing opportunity. She did not forget her boys in Ward E though and she sent them a barrel of picnic delicacies. On September 28, one of them wrote to her: “I received your very affectionate letter addressed to the boys and if you could have been here and seen the attention they paid while reading your letter to them you would ever be proud of them for they will never forget their ministering angel. The weather was fine for the picnic and they appeared to enjoy themselves; as for me I relished everything. The men speak volumes of the nobleness of your generous heart. God Bless you, you generous soul. You are in the prayers of us all.”

After 2 months of visiting relatives in Philadelphia and Salem, Cornelia was anxious to get back to work. With no major military campaigns planned for the upcoming winter months, the Army didn’t need her back yet so she accepted a position at the Contraband Hospital in Washington DC. Contraband was the word used to describe ex-slaves who had been liberated by the Union Army. On November 15, Cornelia wrote home and described the deplorable state of the Contraband Hospital: “Here are gathered the sick from the contraband camps in the northern part of Washington. If I were to describe this hospital (a rough wooden barracks) it would not be believed. We average here one birth per day and have no baby clothes except as we wrap them up in an old piece of muslin, that even being scarce. It is not uncommon to see from 40 to 50 new arrivals each day. They have nothing no one in the north would call clothing. This hospital is a reservoir for all cripples, diseased, aged, wounded, infirm from whatsoever cause; all accidents happening to colored people in all employs around Washington are brought here. It is not uncommon for a colored driver to be pounded nearly to death by some of the white soldiers. A woman was brought here with three children by her side; she said she had been on the road for some time; a more forlorn, wornout looking creature I never beheld. Her four eldest children are still in slavery, her husband is dead. When I first saw her she laid on the floor, leaning against a bed, her children crying around her. One child died almost immediately, the other two are still sick. She seemed to need most, food and rest, and those two comforts we gave her, but clothes she still wants. One of the white guards said that he was going to get paid soon and would give me $5. Two little boys, one 3 years old, had his leg amputated above the knee the cause being his mother, not being allowed to ride inside, became dizzy and dropped him. The other had his leg broken from the same cause. This hospital consists of all the lame, halt and blind escaped from slavery. We have a man and woman here without any feet theirs being so frozen they had to be amputated. Almost all have scars of some description and many have very weak eyes. There were two very fine looking slaves arrived here from Louisiana, one of them had his master’s name branded on his forehead and with him he brought all the instruments of torture that he wore during his 39 years of very hard slavery. He wore an iron collar with 3 prongs standing up so he could not lay down his head; then a contrivance to render one leg entirely stiff and a chain clanking behind him with a bar weighing 50 pounds. This he wore and worked all the time hard. At night they hung a little bell upon the prongs above his head so that if he hid in the bushes it would tinkle and tell his whereabouts. This system of proceeding has been stopped in New Orleans and may God grant that it may cease all over this boasted free land.”

In January of 1864, Cornelia wrote to her brother William: “Where are the people who have been professing such strong abolition proclivity for the last thirty years? Certainly not in Washington laboring with these people whom they have been clamoring to have freed. They are freed now or at least many of them, and herded together in filthy huts, half clothed. And, what is worse than all, guarded over by persons who have not a proper sympathy for them. They are totally ignorant of the mere rudiments of learning, not one in a hundred can read so as to be understood.” Cornelia believed that freedom was useless to the ex slaves without an education. She spent two hours every day teaching Black children how to read and write and held a night school for Black adults every other evening. From a letter Cornelia wrote to her sister Ellen on February 8, 1864 (Cornelia’s birthday): This is the 8th of February. I have lived in this world for 24 years as thee probably knows. It is a most beautiful day here. I am going to teach school today. I went around to all of the shanties yesterday – found many of the contrabands living (they say upon the Lord) without bread and almost naked. I do not go to the hospital now and have plenty of time to attend to their wants. Someone must do it. I hope you will not regret my leaving the hospital for I did stay just as long as I could.” Cornelia had quit the hospital because she could not stand how rudely the patients were being treated. She felt that educating their Race was the best way that she could contribute to them and even though she would soon be back on the battlefields, it was a notion that she would revisit after the war.

The surgeons of the 2nd Corps did not forget Cornelia’s service to them at Gettysburg. They had set up a hospital at Brandy Station, Virginia and on February 10, 1864, they asked Cornelia to join them immediately. She arrived the next day and was assigned to Dr Frederick A Dudley of the 3rd Division, 2nd Corps. Despite being just 23 years old, Dudley was a fantastic surgeon and he was very handsome to boot. The two had first met at Gettysburg when Cornelia brought him something to eat when he was on a 15 minute break from the amputation table. Cornelia spoke of him often in her letters and though she never said so, it is quite clear that she loved him. Cornelia had been at Brandy Station for 3 months when General Grant ordered all civilians to leave the Army. She returned to Philadelphia, living with her sister’s family at 634 Race Street (across the street from Franklin Square). She was only in Philly for a short time when one morning, while on an errand to 7th and Arch, she heard the newsboys crying “The Battle of the Wilderness” and General Hays Killed”. Without completing her errand, Cornelia returned home and told Ellen that she was going to Washington, which she did that evening. Her silver medal from Gettysburg secured her a meeting with Secretary of War Stanton, though he denied her a travel pass thinking the situation was too chaotic for a young woman. Once again Dr Child came to her assistance and got her through the lines as his assistant. They became separated at Belle Plain, Virginia. While Dr Child was helping badly wounded soldiers board steam boats at Belle Plain Wharf, Cornelia had come across a group of walking wounded as she explained in a letter to her sister Ellen: ” It is some date (approx. May 13, 1864) and I am in Fredericksburg city. I do not know where Doctor is. On going ashore at Belle Plain we were met with hordes of wounded soldiers who had been able to walk from the Wilderness battlefield. They were famished for food and as I opened the remains of my lunch basket the soldiers behaved more like ravenous wolves than human beings, so I felt the very first thing to be done was to prepare food in unlimited quantities, so with my past experience in arranging a fire where there seemed no possibility of one, I soon had a long pole hanging full of kettles of steaming hot coffee. and this, with soft bread, was dispensed all night to the tramping soldiers who were filling the steam boats on their return trip to Washington. Soon the long train of ambulances containing severely wounded men commenced arriving and among them the Head Qts ambulance with General Hays’ dead body on its way back to Pittsburgh. I knew this ambulance had to report back to the 2nd Corps hospital and when daylight came I boarded it to go to Fredericksburg where the hospital is established.”

After writing to Ellen, Cornelia wrote to her mother: “I was the first Union woman in the city. We calculate that there are 14,000 wounded in the town; the Secesh (Secessionists) help none, so you may know there is suffering equal to anything anyone ever saw, almost as bad as Gettysburg. I am well, have worked harder than I ever did in my life; there was no food but hard tack to give the men so I turned in and dressed their wounds. It was all that could be done. I am going out on the front to our new Division hospital in a few days but you need not be concerned. I am permanently calculated for getting along under very trying circumstances.”

While in Fredericksburg, Cornelia assisted Dr S Oakley Vanderpool (who was the Surgeon General of New York) in establishing a hospital in the Methodist Church. Vanderpool wrote to an Albany newspaper praising Cornelia’s service and the letter was picked up by the NY Tribune on May 31. In part, Vanderpool wrote: “Were any dying, she sat by to soothe their last moments, to receive the dying messages to friends at home and when it was over, to convey the sad intelligence. Let me rise ever so early, she already preceeded me at work, and during the many long hours of the day she never seemed to grow weary or flag. One can but feebly portray the ministrations of such a person. She belonged to no Association and had no compensation. She commanded respect for she was ladylike and well educated; so quiet and undemonstrative that her presence was hardly noticed except by the smiling faces of the wounded as she passed.”

On May 28, 1864, Cornelia left Fredericksburg, part of a 15 mile long wagon train heading for the front, some 60 miles to the west over many narrow and winding roads. The wagon train was constantly attacked by Confederate guerillas. While on the trail, Cornelia wrote to her sister Ellen on May 31: “We have halted to water the train which is quite a job. If I ever get through this march safely I shall feel thankful. If not, I shall never regret having made the attempt for I am no better to suffer than the thousands who die. I think that the privates in the army who have nothing before them but hard marching, poor fare and terrible fighting are entitled to all the unemployed muscle of the north and they will get mine with a good will during this summer.” On June 2nd, Cornelia arrived at the Union 1st Division, 2nd Corps Hospital at White House Station, Virginia (very near the plantation where George Washington courted Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759). The next day she again wrote to Ellen: “I have turned wound dresser and cleaner generally. You can hardly imagine the appearance of our wounded men now brought in from the field, after having been under fire for 20 successive days. Such fighting never was recorded in any history.” This was during General Grant’s Overland Campaign. His goal was to decimate the Confederate Army with his superior strength of numbers (Grant had about 110,000 soldiers and Lee had just 65,000). The campaign was successful for Grant as 50% of Lee’s men became casualties but the cost of victory was high. More than 7,600 Union soldiers had been killed and another 38,000 were wounded. In her letters home, Cornelia was often critical of General Grant and his ruthless tactics.

In mid June, General Grant laid siege to the City of Petersburg and Cornelia’s hospital was moved to nearby City Point, Virginia. On August 17, 1864, Captain Charles Dod, a wounded Union officer, wrote home to his mother: “Dearest Mother, I came here day before yesterday. I was so much under the influence of opium and quinine and suffering so much pain that I could not write. Today I feel a little better but I fear I will be sick longer than expected. Yesterday I saw a lady about 21 or 22 years old, well dressed and very pretty, coming into the ward. What was my surprise to hear her inquiring if Captain Dod was here. Although lying on my cot in terrible dishabille, I signified that I was the gentleman wanted. It turned out to be Miss Cornelia Hancock, cousin of Henry Smith and Morris Stratton. She said that she felt as if she had known me for a long time and was very glad of an opportunity of serving me. Without my knowing it she solicited permission from Dr Hammond to let me take my meals with her. So at every meal time she sends an orderly who when I am well enough carries me down. She is constantly sending me little delicacies and I feel that it is almost worth while to be sick to obtain such treatment. She is well known and as much beloved in the 2nd Corps as Florence Nightingale was in the British Army. I have the dysentery but not a bad case of it. Your Loving son, Charlie….. P.S. Dr Hammond has just been in and says that I also have intermittent symptoms and prescribed accordingly. Please don’t worry or think of coming down until I stop writing.” Ten days later Cornelia wrote to her mother: “Captain Dod of Henry’s Company died in my bed today. His mother arrived in time to see him just one day and night. He sent for me to come see him in the wards and after he became very ill, in his delirium, he came to my tent and I kept him as long as he lived. He is the first man I ever saw who was fixed up nicely, like he was at home. The scene was very affecting and I shall never forget it. His mother took his pocketbook from his pocket and gave me all that was in it ($100) which she said she knew was the wish of her son. I did not want to take it but she wanted me to buy a remembrance of him and give what I want to the soldiers. So I have the money to keep until such time as I have a house of my own and will buy something nice with it marked with the event of Captain Charles H Dod’s death. He was a splendid looking officer and died a Christian death. He put all of his dependence upon my energies in this world and the Savior for the next. August 27th was the date of Captain Dod’s death (Please preserve this letter for me, Mother).”

Cornelia was very popular with her patients. On September 2 she wrote to her sister Ellen: “I have a present of something almost every day, my watch chain is full of trinkets. Today the boys gave me this piece of chain. I would like it fixed into a good chain for my watch and sent back to me. I want, in the next letter, sent me a lot (1 dozen) rings to attach trinkets of various kinds to my chain, small rings. I lost three articles off of my chain the other day for which I was very sorry.” On September 11, Cornelia wrote to her mother: “Today the wife of one of the soldiers died and he wanted very much to go home. I took his telegram to the surgeon and he said that he would have to forward the request to General Hancock and await his decision. The soldier started to the front with a heavy heart to try his luck, got two miles and commenced raising blood so that he had to come back. I was advised by several surgeons here to go to general grant and get a furlough direct. No military man could go because it was informal and would not be granted. They all had faith in my ability to obtain it and sent me in an ambulance to go and try. I went and had a short interview with Grant’s adjutant general and in two hours time a furlough was in the soldier’s hands for 20 days. My fame has spread the length and breadth of this camp. Such a miracle accomplished in so short a time. All who know me say it is easier to grant my request than to undertake to deny me because I am so persevering. The secret – I do not bother authorities about small things and so all reasonable great requests are granted me.”

Throughout her letters home, Cornelia often mentioned her friend and colleague, Dr Frederick A Dudley. Dudley was a year younger than Cornelia. He was very handsome and despite his age, was a skilled surgeon. Cornelia was very fond of Dudley and it does seem that she loved him, though she never said so. On October 27, 1864, Dudley was captured after the First Battle of Hatchers Run when he volunteered to stay behind with the wounded who could not take part in the Union retreat. He was sent to Libby Prison where he was paroled on January 14, 1865, though he remained in Confederate custody until the end of the war. On December 4th Cornelia wrote to her mother: “If I could only hear from my Doctor I should be much more happy than I am now. Nothing has ever been heard from him. I see they are exchanging prisoners very rapidly from Southern prisons. I do not believe that he went further south than Libby. I have hope that Fred (before this he was always Dr Dudley….now she used his first name) will be put upon duty in some hospital. They will soon find that he is a good operator. If so he will fare well. Nothing but conjecture can fill our minds, nothing definite is known except he was left upon the field at 10 o’clock at night in charge of our wounded.” Then on December 14th she wrote; “I received a letter from Dr Dudley’s mother, she thinks that he is dead. I shall never think so, even if he never comes back. Send me that letter of Doctor Dudley’s that is laying around your house somewhere I Hope. I want it.”

The Confederacy rapidly fell apart by the Spring of 1865. On April 3rd, Cornelia wrote to her mother: “This morning we could see the flames of Petersburg lighting the skies. We can see flashes from the firing and there is a deafening roar. The question in all of our minds is ‘Will the rebels take breakfast with us or we with them?’ ” On April 11th she wrote to her sister, Ellen, “Richmond is taken. I visited the city on April 9th and saw for myself that General Weitzel has his headquarters in Jeff’s mansion (Confederate President Jefferson Davis). The lower part of the city was smouldering with a fire started by the Rebels before leaving. The white people were all hidden away in their houses but the colored people were jubilant and on the streets in gay attire. We visited Libby Prison that was at this time filled with Rebel prisoners. Flowers were blooming and the weather was mild. Beauty was apparent even in the dejected desolate city. We saw Jeff Davis’ HQ but no Jeff Davis. Lee has now surrendered. We were wholly unconscious of it until we returned to City Point, when the great rejoicing at General Grant’s HQ proclaimed the fact. The salutes were fired here yesterday at noon. A bloodless surrender keeps our hospital empty and we have time to give special attention to a few who are dying just when they want most to live. President Lincoln visited our hospital a few days since. He assured us that the war would be over in 6 weeks.” (Lincoln was assassinated later that week).

In May of 1865, Cornelia was sent to Alexandria, Virginia to help establish a resting place for the tired and sick of the 2nd Corps. On May 13, she wrote a letter to her sister in which she said that she was looking forward to Dr Dudley joining her there soon. After reading through Cornelia’s letters, I had expected that perhaps she and Dudley would marry after the war but it was not to be. Dudley planned to go into private practice in New Haven, Connecticut while Cornelia planned to school Negro children in the South. On May 23 and 24 of 1865, a Grand Review of the Troops was held in Washington DC. Cornelia was there to take part in the celebration as she later wrote: “On the first day’s review (May 23) in Washington I saw the Army of the Potomac from the piazza of a country house where I could speak to those I knew. When Sherman’s Army passed (May 24) I was on the President’s Grand Stand and saw general Sherman as he passed from the Treasury Building to the White House – the only moving figure – he was mounted on a fine black horse, with all the bands playing ‘Hail to the Chief, the conquering hero comes’. That very afternoon I returned to Philadelphia.”

From her experiences at the Contraband Hospital, Cornelia firmly believed that the Negro Race would never rise in the world without an education. In 1866, with the support of the Friends Association of Philadelphia for the Aid and Elevation of Freedmen, she established the Laing School for Negroes in Mt Pleasant, South Carolina. Cornelia originally applied for a piece of land next to the Episcopal church but the congregants feared that the sound of Negro children would disrupt their services, so she was given another plot of land instead (overlooking the harbor at Charleston with Fort Sumter in view). The land was granted for 99 years and the school building was completed in 1869 (closed in 1970 after schools were desegregated). The school was open for 8 months a year for children ages 5 to 17. Cornelia made frequent visits to Philadelphia via steam boats and spent her off months living in Salem with her parents. She taught at the Laing School until 1878 when she returned home to Salem to care for her father who was ill. He died on July 7, 1878. After her father’s death, Cornelia moved in with the family of her cousin, Elizabeth Nicholson Garrett at 456 Franklin Street (the block no longer exists….it was located south west of 7th and Spring Garden Streets).

Now back in Philly, Cornelia realized that there was much charity needed at home. Along with her brother in law, Dr Child, and other like minded citizens, Cornelia helped to form the Society for Obtaining Charity and was appointed to be the Society’s Superintendent for the Sixth Ward. She also helped to establish the Children’s Aid Society and volunteered at the Bureau of Information. During the winter of 1884/85 many unemployed men applied to Cornelia for charity. During the first week of January, 1885, she came up with an idea to make these men self sufficient. She supplied them with brooms and kettles and assigned them each an intersection along Market Street between 2nd and 6th Streets. Their job, she told them, was to keep the intersections clear of mud and slush for the comfort and convenience of society. The kettles were tied to the nearest lamppost or telegraph pole with a sign that read ‘Please Donate to the Street Cleaner”. When asked by a reporter how he was making out, the man sweeping 3rd and Market beamed that he had made 58 cents (equivalent to $16 today).

On May 31, 1889, the South Fork Dam broke, flooding Johnstown, Pennsylvania with 20 million tons of water. More than 2200 people were killed including 99 entire families. Nearly 100 children were left orphaned. Cornelia along with Helen Wallace Hinckley (a fellow Board Member at the Children’s Aid Society) caught the first available train to Johnstown and arrived there on June 7. Within a half hour after arriving, they established the Waif’s Mission and took charge of the orphans. For some of the children they were able to locate relations but many were sent to orphanages across Pennsylvania, Ohio and New York. Cornelia and Helen remained in Johnstown until the last orphan had a place to go.

Cornelia often received letters from her old Civil War patients inquiring as to how she had been and she was always delighted to hear from them. Sometimes she would visit the Civil War Vets who were living at the almshouse. Cornelia was the Secretary (later President) of the National Association of Army Nurses and often represented the group at the various GAR conventions, always wearing her Gettysburg medal and her chain of soldier’s charms. On May 1, 1898 (the first week of the Spanish American War), Cornelia and her fellow Civil War nurses of the National Association of Army Nurses announced that they were ready to serve again and were awaiting orders with the battlecry “Here I Am”. The call never came but their offer did contribute to the wave of patriotism spreading through the Country. In September of 1899, Philadelphia was the scene of the GAR National Encampment and Cornelia’s Army Nurse group was asked to serve as Hostesses. No hostess was more sought out than Cornelia who was still very much beloved by 2nd Corps veterans. On October 4, the New Haven Register ran a story about the Encampment which included a nice piece about Cornelia. New Haven was the home of Dr Dudley who I like to think smiled as he read that morning about his favorite nurse.

In 1903, Cornelia traveled to San Francisco (three years before the big earthquake) to attend the 37th GAR National Encampment. On August 22, 1903, The San Francisco Chronicle reported: “An Army nurse of the Civil War who has been attracting unusual attention, and some from the very men whom she nursed and comforted upon the field of battle is Miss Cornelia Hancock. She was the first woman who reached and ministered to the wounded of the 2nd Army Corps on the bloody field of Gettysburg. She has a large collection of tokens and momentoes given her by the “boys” for whom she cared. Often she was under fire. Once a cannonball passed between her and another nurse with whom she was talking. On another occasion a shell struck the back of a carriage in which she was riding.”

Now in her mid 60’s, Cornelia donated her time to the Colored Settlement House at 922 Locust Street. Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday afternoon, she would take a group of 25 youths out to earn money by sweeping the alleys and courts between Walnut, Spruce, 9th and Broad. She would pay them 5 cents each per street swept. She inspected all of their work and if a job was not done thoroughly it had to be done over. In December of 1906 Cornelia told the Philadelphia North American: “The combined beauties of this work is that it develops in the children a sense of civic pride and the quality of thoroughness. If they are ever property owners or have homes to care for they will not shirk their responsibilities to themselves and the community at large.”

Cornelia’s sister, Ellen Child, with whom she lived at 634 Race Street, died on January 31, 1907. Cornelia continued to live at that address until 1909 when she moved to 120 N 19th Street along with her two spinster nieces, Isabella and Elizabeth Child. During the first week of July in 1913, Cornelia attended the 50th Anniversary Gettysburg reunion as the guest of Mrs Salome Myers Stewart (in 1863 Salome was the town school teacher who opened her home to wounded soldiers). More than 50,000 veterans attended the event. If you look at the photograph of her taken at Gettysburg you will notice that she is wearing the silver medal and the chain of charms that were presented to her during the war. In May of 1917, Cornelia now 77 years old, travelled to Washington DC as an invited guest to the dedication of the new Red Cross building. It was reported that she donated an interesting collection to the Red Cross museum.

Cornelia spent her last years in retirement living with a niece in Atlantic City, New Jersey. She died there on December 31, 1927 from nephritis. On Cornelia’s nightstand, her niece found a bound packet of old letters with a note attached that read “Burn without reading”. Who the letters were from and what words they contained is anyone’s guess. Perhaps they were love letters written long ago by her Dr Dudley? The dutiful niece burned them so we shall never know. Cornelia rests with her parents at Cedar Hills Friends Cemetery, Harmersville, Salem County, New Jersey. In 1937, Cornelia’s letters home were complied into a book by her great niece entitled South After Gettysburg and it became a best seller.

researched and written by Bob McNulty July 10, 2016. For more stories go to:https://www.facebook.com/